Background

In this Freedom Project case, I, Guru Sanju, was working with Aycan, one of my schizophrenic patients whose brain and nervous system had been deeply affected over time. Her dream was to come with me to the mountains for an intense physical project in extreme climate. But before the body can climb, it has to eat, digest, and grow strong.

So I designed her very first Freedom Project session not as a “talk” but as a live, practical training: learning to cook and eat a simple, powerful Nepali thali—dal, bhaat, and bhaji—in my energetic presence. For the next thirty days, my intention was to adapt her body, brain, and nervous system to this food, so her system would receive complete nutrition and stamina from it. In this discourse, I describe, in detail, how I guided her step by step, how dal-bhaat became medicine for her brain, and why the Nepalese slogan “Dal-Bhaat Power – 24 Hours” is not just a saying, but a living reality for mountain people.

Purpose of the Session and Preparation

The purpose of the session that day was to begin teaching Aycan how to survive in the mountains.

The starting action was very simple and very powerful: learn to cook.

I told her clearly that for the next thirty days I would teach her only cooking—different kinds of food in my presence—so that her body would adapt to eating these foods. This was not just culinary training; it was brain and nervous system rehabilitation disguised as a daily meal.

For this first session, the preparation was:

- She would learn to create a simple Nepali thali.

- She had to collect the ingredients and be ready by the time the session started.

- She would cook the food in my presence.

The menu for the day was:

- Dal (lentils)

- Bhaat (rice)

- Bhaji (vegetables)

I told her she could watch any video beforehand just to get an idea of the ingredients and look up Indian-style versions of the same menu to begin with.

One important instruction was: one hour before the session, she would show me all the ingredients she had collected. If anything else was needed, I would ask her to arrange it.

Welcoming Aycan into the Freedom Project

When the session began, I greeted her playfully:

“Yes. Miss chef is ready for today’s session. How are you feeling with this?”

Then I formally welcomed her:

“First of all, welcome to the Freedom Project for these hundred days. This will be totally different from what you have experienced so far. Every time there is a session, you will move forward. Your energy will move forward.”

I made it clear that all of this was preparation for the mountains.

I told her that first of all, I was taking her to a state where she would be confident:

“I am going to the mountains.”

That should be the attitude.

Secondly, I reminded her that her business, her brain, and her nervous system also needed to know:

“Yes, I am going to the mountain, which was my dream once, which was your inner GPS.”

And I told her very clearly that she was going only because her energy was calling:

“While you are going, because your energy is calling, that is why you are going. Otherwise, there is not a single force on the earth that can make it happen. Only I can make it happen—whatever is in your destiny.”

I emphasized that this understanding was important for us to move forward.

Then I invited her into action:

“Now, you can share with me what you want to cook today. Yes, yes.”

Choosing the Mountain Menu: Nepali Thali

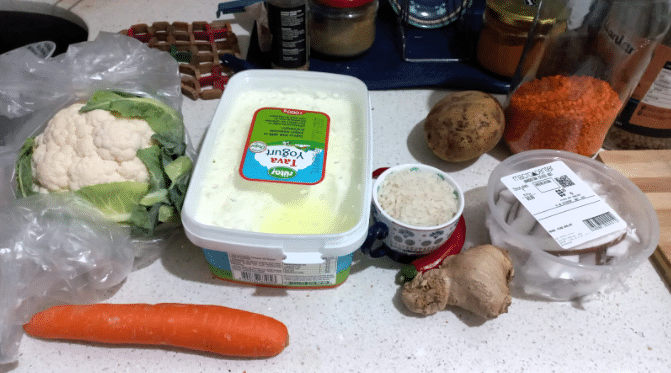

She showed me what she had:

Red lentils.

Black lentils.

Potato.

Garlic.

Onion.

Mexican chili pepper.

Cauliflower.

Ginger.

Rice.

And even some sugar lying there.

I guided her:

“We are going to prepare Nepali thali. Nepali thali means a meal which is cooked by Nepalese people in the Himalayas. The basic meal consists of rice, then dal—that means lentils which, after the cooking process, become yellow lentils—and some vegetables.”

I told her I was excited for it and instructed her:

“You will be sharing with me whatever you are doing in the process. If I feel I need to give you any instructions, then I will give you. Yes. Yes, yes, yes. If it is comfortable for you.”

We clarified the rice:

“No, plain rice. It is called plain rice. The name of the meal is plain rice when we cook it, or in Nepalese thali, it is called bhaat.”

Then I explained the name of the whole meal, spelling it out:

“The name of the meal is dal-bhaat-bhaji. Dal-bhaat-bhaji. It’s like the way Chinese noodles we call every meal by a name, isn’t it? So this meal is called dal-bhaat-bhaji.”

Cooking the Rice: Light, Fluffy, and Strong

I guided her through the rice step by step.

“Wash it two to three times so that all the extra starch sticking to the rice comes out. Yes, I think it’s all right.”

I asked her if she was finding the process interesting.

Then I taught her a mountain proverb:

“There is a famous saying in Nepal: they say Dal power, 24 hour. This means that it is very, very strengthening food. When you eat dal-bhaat, it is very good. It builds your stamina. So: dal-bhaat power, 24 hour. It is like that. So I am going to make you stronger before you go there.”

I instructed her to use about double the water for the rice:

“Two times more water. Yes, good. It should not be sticky. It should be a dry one. Just like pulao you cook, the rice should be very much lighter and fluffy.”

I checked:

“You have put double the water? Yes, the water is all right.”

I reminded her again:

“You have to boil the rice and it has to be a fluffy one, not liquid and soupy. So pour the water accordingly.”

At some point, the video connection became unclear, and I told her:

“Is your network not good? I am unable to see you properly. Yes. All right, I can listen to you. You can continue.”

Preparing and Washing the Lentils

Then we shifted to the lentils.

“Lentils. So first, you wash the lentils. When you are washing the lentils, make sure you are making use of both your hands to wash them. Make use of both hands and wash them three to four times until the colour of the water becomes very transparent.”

I explained what she would see:

“Initially, the water will become like white-coloured water. This means that, again, the extra fertilizers or pesticides from the food you are washing are being removed, and you are making it completely pesticide free. So three to four washes are important.”

I encouraged her to keep doing mouth exhalation while working:

“And keep doing mouth exhalation. Very good.”

She had another kind of lentil at home, and I told her:

“You showed me that you have another quality of lentil. You can mix both of them and make it together, because it will become more nutritious. Another lentil variety you can also mix. Yes.”

Building the Healing Dal

I asked her:

“One more time. And then, what is your idea to cook it? How will you cook it? Share with me, then I will tell you the process if I have any corrections.”

She shared her idea, and I corrected it gently:

“No, no, that is not the process. I will share with you the actual traditional way, where it will become a little tastier also and you will love it. And it will become nutritious also.”

I guided her precisely:

“After you wash it, pour water in it—double its quantity—and then bring it in front of the camera and I will tell you what to do next.”

I had her wash it again:

“Yes, one more time. And then the fifth time, you pour water in it. Then bring the lentils. Yes.”

I told her:

“Now you add water in it, double—wherever you are going to cook it, in that utensil you transfer it. Or if you are doing it in the same utensil, then it’s okay. So wherever you are going to cook now in this utensil—correct.”

I refined the water level:

“A little bit more. It will take a little bit more. I want you to have a little soupy lentils, dal which you can drink also. It is healthier and you will feel better. It is strengthening when you drink it; your digestion is better if you drink the dal like a soup. So a little more water.”

She added more, and I said:

“Yes, a little more water is required. Yes, yes, yes.”

Then I stopped her:

“No, no, the process is incomplete. Bring it here. I will tell you what to do when you are putting this to boil.”

Adding Ginger, Spices, and Healthy Fats

I taught her the flavour and medicinal base of the dal:

“When you are putting the dal to boil, you need to put some turmeric in it. Cut some ginger. Yes, ginger. What do you call it in Turkish?”

She replied, and I repeated:

“Vanzetti? Okay, so I learned Turkish now. So, vanzetti. You cut it into small pieces, remove the cover. Yes, yes. This much is enough. Remove the cover. Yes, you take the fresh one.”

I summarized the sequence:

“So first you washed the dal. Then you put water—double the amount of the dal. And now you will put ginger in it, cut into small pieces. Yes. Great. Now put it in the dal. Yes, put it in the dal.”

Then I added the spices:

“Now add two tablespoons of turmeric powder and a little of cumin powder. Yes, two tablespoons. Yes, this much is enough. Now this is enough. Just with the idea—yes, this much is enough. Cooking is more intuitive: with ideas, you can cook.”

Then I asked about fat:

“Now take some—do you have oil with you? Cooking oil? Yes. Olive oil? Okay. You can put one spoon of olive oil in the dal.”

I checked for ghee:

“And do you have ghee, clarified butter? Do you have clarified butter? Put one tablespoon in it. Yes, very good.”

I guided her:

“Put one tablespoon. Yes, this much is enough. And when you eat it, then also you put some ghee into the dal and eat it. It is very healthy. All right. When you eat the meal, at that time also you put some clarified butter—this ghee—into the dal and eat it.”

Then I added one more ingredient:

“Now one more ingredient you will add: do you have tomatoes at home? Tomatoes? Do you have? Yes, bring one tomato.”

She didn’t have a whole one, so I said:

“Whatever you have—if you have smashed one, you can bring that. I do not need the paste; I just need the whole tomato. Yes, yes. Two tomatoes—you can cut them into four pieces and put them into the dal. Put them in the dal. And also chili—half a chili you can put. If your taste buds don’t allow chili, then you can put half chili, but it will be very mild. Yes.”

I asked again:

“Tomatoes—did you cut? Yes. Cut them into four pieces and put them in the dal. Yes.”

Food as Lubrication for Bones and Nervous System

I explained why this kind of cooking was important for her:

“Most of the food that you eat is actually boiled food. And that is not strengthening your nervous system. Slowly, slowly, slowly I will introduce some kind of process where the food will be tasty, healthier, and yet not too mild. A little bit of oil is required for your lubrication.”

I told her:

“Your bones and nervous system rejuvenate. Your bones need a lot of lubrication, and that is supplied by oil and ghee—clarified butter or normal butter—cheese, milk, curd, all these things. So lubrication is required for a healthy body.”

Letting the Dal and Rice Cook with Awareness

I told her:

“In between, while you are cooking the dal, you do not need to listen to me every second. Just continue with it. I am just narrating.”

I explained why I was narrating:

“I am just narrating everything you are doing so that later, when you recall this process, you can remember each step.”

I reminded her to keep an eye on the rice:

“So while you are cooking the rice or cooking the dal, have a look at the rice. Is it in the process, in the making? Good? Then all right.”

I instructed:

“Now you have to close the lid. Yes. Now for the dal, you need to put it on the oven—means gas or whatever you have.”

Then I gave her an important rule about salt:

“No salt. You never put salt when you are boiling dal. The water becomes hard water when you add salt to it, and it becomes very difficult for the boiling process. It takes too much of electricity or your fire energy, heat energy. So it becomes hard water and the lentils do not boil.”

I continued:

“So salt you will add later, after your boiling process is over and it is finely cooked. All right.”

I generalised:

“Whenever you boil something, anything you put for boiling, at that time don’t add salt—especially for lentils, because lentils are very hard. When you add salt to the water, they do not boil. So mostly salt is added at the end of the cooking process so that everything is cooked—in terms of vegetables also. In terms of vegetables also, add salt a little later. Yes.”

On rice, I said:

“For rice, do not put salt. It is not required. It is not a salty rice. It is plain, plain rice.”

Then I summarised the boiling time:

“Now put the dal for the process of boiling, and it will take at least twenty minutes with this process to be cooked. Yes.”

The Secret of Steaming and Nutritional Value

I told her:

“All right, all right. Now this dal will be boiled, and after that, there is one process which I will teach you beforehand. Because in this session, there may not be time, but after the session, you will do this activity.”

I explained the name:

“It is called tadka dal. That is like you are adding some oil and some spices into it and adding it to the dal for that extra flavour, for making it tasty, because your taste buds need to be activated.”

I reminded her:

“Your tongue has all the taste buds, so this process will add the taste to the dal. You will feel like eating more. All right—it means your taste buds will be activated.”

Before tadka, I gave her an important rule about steaming:

“When the dal is cooked, then let it be in steamed mode for some time, and then open the lid only after the steam is over. Maybe for the next twenty minutes you can keep it like that. When the dal is cooked in a steamed manner, it has more nutrition locked in it.”

I clarified:

“So keep doing that. Don’t open the lid immediately. Got it?”

I explained the logic:

“In the steam itself, it gets cooked better. Better means it will be bigger, more swollen. The more it is cooked, the more digestible it will be in your body. That is the purpose. And when it is cooked in the steam, the nutritional value of the food remains with it.”

I contrasted fire vs. steam:

“When it is cooked directly in flame, the nutrition in the food goes away—means it evaporates. It’s like that. But when it is steamed, then the nutritional value remains with the food. This is like basic chemistry: if you cook something with fire, then the nutrition goes away, it burns. But when you cook it with steam, in low flame, then it cooks and the nutritional value of the food remains. So have it slow cooking. No need to make it fast. Make it slower.”

Preparing the Tadka for Dal

I then guided her into the tadka process:

“After this, when you open the lid, you can send me the photo and mix the seasoning that you have made ready. That seasoning of onion and tomato—you need to burn it a little, mix it, make it very crispy, like you make French fries, that kind of crispiness. It should be fried crispy.”

I completed the instruction:

“And when it becomes crispy, then you mix this mixture into the dal, and then mix the whole and cook the dal for a few more minutes on slow flame. Okay. That you do. This is dal complete.”

I summarised:

“So rice is complete. Dal is complete. After that, what you are going to do—you will cook vegetable.”

Cutting and Seasoning for Dal and Vegetables

Now I turned back to the tadka ingredients:

“For that, you will take a pan. Do you have whole cumin with you? Whole cumin? Let me see that. Let me guide you. One second. You have shared with me the ingredients. I will check and tell you what to do.”

I looked at her ingredients:

“You have oregano, chili pepper—that you bring. Oregano, chili pepper, curry. Yes.”

I told her:

“Take a little bit of pepper, cut it into small pieces. Enough. Cut it into small pieces.”

Then I instructed:

“Then take some onion. Take one onion. Yes.”

She asked about the name of the process, and I told her:

“It has no other name. You have to learn it. It is called tadka. It has no other substitute name because this process is only made in Indian food—dal—and Nepalese food.”

I added:

“Now take some tomato. One tomato you take. Yes. One tomato and one onion. One tomato. Yes.”

I specified:

“Cut them into small pieces. Very small pieces. Correct. Very small pieces.”

I extended the session time consciously:

“Yes. Small pieces—done. Onion also. I am extending the session time a few more minutes till your process is done. Next session I will conduct later, a small one. Okay? Because I want success to happen. You should feel that sense of achievement today after doing this.”

I even coached her on chopping technique:

“It has a technique. Onion—cut the onion like this. Chop the onion like this. If you are unable to chop it into smaller pieces, then leave it in bigger pieces also. That is the skill you will learn. Yes, correct. Correct. Small, small pieces.”

Then I showed her how to divide the ingredients:

“Now, whatever you have cut—all the things—we will divide into two portions. Because I will teach you to cook the vegetable also. And all these ingredients are common to both dal and the vegetable. So you can divide them into two parts. For the dal you can keep a little bit, for the vegetable you can keep the rest. Yes, yes—enough. Like this, you can divide.”

Making the Tadka: Heating Oil and Herbs

I instructed her:

“Now add some oil to the pan. Heat the pan, add some oil.”

I reminded her:

“In the meantime, look at the rice—if it is cooked.”

Then I described the tadka flavour:

“Let the oil burn in. This is for the oil—I’m making it a third cup, like a base. Do you have any pizza seasoning or anything like that? Do you have herbs? Yes, that will do.”

I told her:

“So put some herbs in it and heat it. Yes. Black pepper or anything which is used as a seasoning—all these things you put in. And salt also—salt, turmeric, a little turmeric. Put a little turmeric. Yes, one-fourth spoon. Yes.”

I added:

“Yes, this much you need to cook. And chili also—chili. Do you have cut chilies? A little bit of this chili means you are making it tasty. When you have coriander leaves and other things like curry leaves, all these things you can put.”

I reminded her:

“So all the qualities of the herbs are going into the food, and this makes your taste buds activate. Now this you need to cook and heat until a smoky flavour comes. Just heat it a little bit more. Yes. Heat it on the flame.”

Managing Time and Steam for Dal

I could see the timing:

“The dal will take more time. So what you will do—I will guide you what to do. These things you will cook now on your own, so that you will get the time and do not have to panic that you have to cook very fast.”

I gave her the timing:

“When the dal is cooked, then let it be in steam mode for some time, and then open the lid only after the steam is over. Maybe for the next twenty minutes you can keep it like that. When the dal is cooked in a steamed manner, it has more nutrition locked in it. Okay? So keep doing that. Don’t open the lid immediately. Got it?”

I repeated the principle:

“In the steam itself it gets cooked better—better means the dal grains will be bigger, more soft. The more it is cooked, the more easily it will be digested in your body. That is the purpose.”

I again explained the chemistry:

“And when it is cooked in the steam, the nutritional value of the food remains with it. When it is cooked in flame, the nutrition in the food goes away—means it evaporates. But when it is steamed, then the nutritional value remains with the food. This is basic chemistry: if you cook something with direct fire, then the nutrition goes away, it burns. But when you cook it with steam, in low flame, then it cooks and the nutritional value remains.”

I summed it:

“So have it slow cooking. No need to make it fast. Make it slower.”

Completing the Dal and Moving to Vegetables

I repeated the instruction for after the dal is done:

“Now after this, when you open the lid, you can send me the photo and mix the seasoning that you have made ready—that seasoning of onion, tomato. You need to burn it, mix it, make it very crispy, like French fries. That kind of crispiness—it should be fried crispy.”

I completed the method:

“And when it becomes crispy, then you mix this mixture into the dal, and then mix the whole and cook the dal for a few more minutes on slow flame. Okay. That you do. This is dal complete.”

Then I confirmed:

“So rice is complete. Dal is complete. After that, what you are going to do—you will cook the vegetable. Now, in my presence, you can start the process: whatever you have, take another pan.”

Then I noticed the time:

“It will take you time to cut all this, so just follow the instructions I give you. You can cook it and show me the pictures step by step. You can show me the pictures and I will guide you if you need any assistance. Otherwise, you can do it on your own.”

Stir-Fried Vegetables: Not Soupy, but Strong

I taught her the vegetable style:

“You can cut the vegetables into pieces in the shape that you love to eat. For example…”

I let her choose the shapes and vegetables.

Then I told her:

“Whatever you want to take, you take it. Then, the same way, this seasoning which you have made ready—put turmeric into it. Salt—salt you will add at the end—but turmeric you will put, and all this mixture you will put, and with a little oil you will keep stirring it.”

I defined the style:

“Stir-fry vegetables. It is not a soupy vegetable. Got it? It will be a stir-fry vegetable. Yes.”

I added a specific vegetable:

“Just a little bit of cauliflower—you take cauliflower. Yes. Sauté. Good. Sauté, sauté, and keep cooking it till it is cooked and ready to eat. It should be a little bit soft, cooked, and not raw.”

I reminded her of the spices:

“A little turmeric and a little bit of chili, then cumin powder—all those things, all the spices, whatever you feel you should add to have taste. Then you cook this.”

I gave her a time frame:

“It will take a total of thirty minutes for you to do all of this activity. You do it; after that, send me the pictures of each and then eat it. Daytime, you can heat the food again and that is it.”

Daily Practice: Eating for Brain and Mountain Strength

I gave her a core daily discipline:

“This food you will eat at least once a day. Every time you will change the vegetables and a little bit of change in the spices and all.”

Then I assigned her learning task:

“You will now start watching videos of how to cook this meal—different ways to cook this meal—and keep experimenting daily with different kinds of experiments. You can teach your brain to cook different kinds of dal—watch it, then experiment it. This is what you need to do throughout the month. All right.”

I promised her the next step:

“Next time I will teach you to make chapatis, rotis—roti, chapati, Indian bread, Nepalese bread, roti. That I will teach you in the next session.”

Closing the Live Session

Finally, I closed the call with warmth and structure:

“All right. Yes. All right. The rest of the communication you do on WhatsApp. And good student—I liked today’s session. Did you? Yes. All right. Bye, bye, bye. See you.”

Reflection on the First Freedom Project Session

Afterwards, I shared a reflection on what had just happened:

“This was Freedom Project first session with one of my schizophrenic patients, who was learning to cook dal-bhaat-bhaji. Dal is lentils, bhaat is rice, and bhaji is vegetable—a combination of food which is eaten in the mountains for strength.”

I explained the long-term vision:

“After three months or hundred days of the project, when she is coming to the mountain for the physical project, she will be strong enough and have the stamina to do the project in the mountains, in the extreme climates.”

I described how she was learning:

“That is how she is going—she is learning in my presence. I am energizing her.”

Then I spoke to others who might be reading:

“And if you too are having any kind of brain and nervous system issues, you can connect to my team and they will guide you further. All right. Have a great day and bye-bye. Thank you.”

I repeated the Nepalese slogan that holds the essence of this food:

“‘Dal-Bhaat Power – 24 Hours’—this is the slogan of Nepalese people who have had high stamina for mountains since ages.”

Post-Session WhatsApp Exchange and Healing Insight

Later, on WhatsApp, the conversation continued.

I wrote to her:

“Wow! Awesome and congratulations

Eat it when you feel extremely hungry and eat consciously. Eat everything hot.

The menu name is: Dal–Bhaat–Bhaji with Dahi (Rice–Lentils–Vegetables–Curd).”

Aycan replied:

“I will eat now.”

I asked:

“Let me know, how was the food?”

Then I gave her a clear six-day task:

“Your next six days’ task is to watch different videos and learn to cook different types of this menu with little modifications, and buy the ingredients and learn the art of cooking and eating. Notice the difference in your body strength gradually.”

After eating, she wrote:

“After eating, I felt the energy at my head area. I liked that feeling. Unique meal it was.”

I responded:

“Brilliant. This is healing. You have supplied a complete meal with all the nutrition to your brain.”

And again, I reminded her:

“‘Dal-Bhaat Power – 24 Hours’—this is the slogan of Nepalese people who have high stamina for mountains since ages.”

Through this one simple, instinctive session—washing rice and lentils, adding ginger, turmeric, oil, and ghee, slow-cooking with steam, stir-frying vegetables, and eating hot, consciously—we had begun to retrain her brain, nervous system, and body for mountain stamina and for life.